Alternative title: why my program needs 1267650600228229401496703205376 gigabytes of RAM to (fail to) compile

Alternative2 title: Boring Coworker? Make Their Laptop Unresponsive For Fun And Profit

Alternative3 title: why recursion limit is not enough

Alternative4 title: recursion limit? We don't do that here

Alternative5 title: [see Alternative title]

Introduction

I love Rust declarative macros. They allow performing super elegant code transformations. They are so powerful that we can use them to parse literally anything, but their core syntax is so simple that one could write their first macro in less than an hour.

The downside of this is that... well... these macros are too powerful. Once they get very complex, a single typo can take hours to be fixed. Even worse, it can drive your compiler crazy. Today, we'll see how one can turn rustc into an unbounded memory allocator stresstest.

Background - a handful of cursed macros

I won't get into too many details there. I'll present the actual macros in a later blogpost.

At a very high level, this macro was recursive. It captured every token passed to it, processed the first tokens, and called itself again with the remaining, unprocessed tokens as arguments.

We have a fancy word for this: TT muncher.

Guaranteeing that a program terminates

It's kinda easy to accidentally create code that never stops and just basically hangs the program. Some languages are designed so that the compiler can detect and reject any code which may hang the program. Rust designers decided it was ok to hang. Sometimes.

In the whole lifetime of a Rust crate, there are two very distinct steps at which different pieces of code are run. At compile-time, the macros are expanded, while at runtime, macro-expanded Rust code is run.

Macros in Rust are defined using a specific language that maps quite well to a purely functional programming language, where mutability and side effects are disallowed. As this language makes extensive use of recursion, there's a very elegant way to make sure that macros expansion actually terminates: the compiler tries to expand the macro, but if too many recursions are performed, then it just stops, telling that some kind of limit has been reached. This way, we are guaranteed that macros eventually stop expanding, and nobody should ever write an overly specific blogpost about macros allocating memory indefinitely.

Regular Rust code is... well... one loop {} away from hanging forever. Hanging at runtime is something we may want to happen. For instance, a REST backend may spend a few milliseconds waiting for an incoming request, dispatch it to a thread, and go back to its initial idle state.

Getting our hands dirty with macros

It is quite easy to write a function that never finishes: just replace its body with loop {}, and we're good to go. Similarly, one can easily write a macro that calls itself.

Something like (playground link):

macro_rules! never_stops_compiling {

() => {

never_stops_compiling!()

};

}

fn main() {

never_stops_compiling!();

}

One can then mentally figure out that expanding this call to never_stops_compiling! ends up indefinitely recursing. As a result, the recursion limit should be reached, and an error should be emitted. Let's check this out:

error: recursion limit reached while expanding `never_stops_compiling!`

--> src/main.rs:3:9

|

3 | never_stops_compiling!()

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

...

8 | never_stops_compiling!();

| ------------------------ in this macro invocation

|

= help: consider increasing the recursion limit by adding a `#![recursion_limit = "256"]` attribute to your crate (`playground`)

= note: this error originates in the macro `never_stops_compiling` (in Nightly builds, run with -Z macro-backtrace for more info)

error: could not compile `playground` due to previous error

This means that the only way to make the compiler use a lot of memory using macros is to maximize the amount of work to perform at each recursion. This way, processing the macro call costs more and more resources to the host machine, making the compiler eventually hang.

The most intuitive way to do this is to add a new token each time we recurse. Something like:

macro_rules! never_stops_compiling {

( $( $input:tt )* ) => {

never_stops_compiling!( $( $input )* | )

};

}

This means that calling never_stops_compiling with no argument will yield to calling never_stops_compiling!(|), which will itself trigger a call to never_stops_compiling!(||), expanding to never_stops_compiling!(|||), and so on, and so forth, adding one | at each recursion. As a result, memory usage increases somewhat linearly at each recursion.

As our goal is to eat all the available RAM, we need to create as many tokens as possible before recursing, so that memory usage increases so quickly that rustc gets OOM killed before the recursion limit is reached. To do so, we need to create a lot of tokens, very quickly.

Exponential growth

Disclaimer: this section briefly talks about Covid-19. Feel free to skip to the next section if necessary.

This post is written in summer 2022. Covid-19 drastically changed our lives more than two years ago. I think everyone here heard at least once about exponential growth.

When a value grows exponentially, this means that it is multiplied by some constant factor at each step. In epidemiology, we call this factor R. It can be interpreted as "each person who catches Covid transmits it to R people". Our goal is to keep this value lower than 1.

Exponential growth has a nice property. As long as we have R > 1, it is guaranteed to eventually grow faster than any polynomial value. This makes exponential growth a strong candidate for our memory hog.

Gimme gimme gimme [tokens]

Let's double the number of tokens passed at each invocation:

macro_rules! never_stops_compiling {

( $( $input:tt )* ) => {

never_stops_compiling!(

$( $input )*

$( $input )*

)

};

}

We need to provide the initial | token so that it is actually repeated:

macro_rules! never_stops_compiling {

() => {

never_stops_compiling!( | )

};

( $( $input:tt )* ) => {

never_stops_compiling!(

$( $input )*

$( $input )*

)

};

}

This means that expanding never_stops_compiling!() will give us never_stops_commpiling!(|), which expands to never_stops_compiling(||), which expands to never_stops_compiling(||||), doubling the number of | at each recursion. As a result, there are 1024 | for rustc to store in the 10th recursion (or 11th, depending on if you want to be off-by-one or not).

In Rust, the default recursion limit is 128. This means that the last call of never_stops_compiling! would pass 2128 (or 2127) tokens before hitting the recursion limit.

Let's suppose we have an awesome compiler. It is running on bare metal, without any kernel that's consuming memory. There is no other process running in the background, all the memory is available. The compiler is so optimized that each token takes one byte of RAM.

We would still need *waves in the air* about 2128 bytes of memory before being able to emit the recursion limit error. That's roughly 10100 GB of RAM. As a matter of fact, the laptop I'm writing this blogpost with has 16 GB of RAM and that's enough for most of my work (looking at you, tremor-runtime).

Let's be honest. No developer on this planet has enough RAM on their computer to make this program fail to compile.

Let's see it in action:

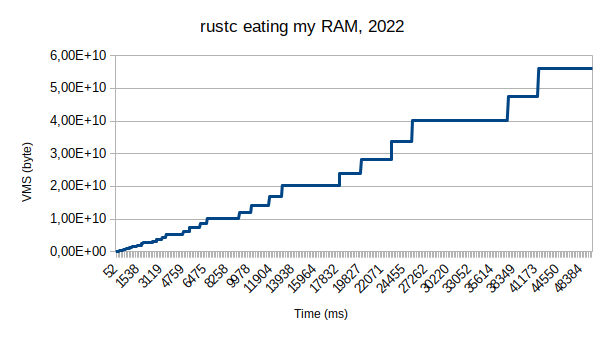

So yeah, that's a lot of RAM.

How did we get here?

I have to confess something: I love declarative macros. Probably a bit too much. I love them so much that I often stay up very late at night, trying to write cursed macros which parses cursed things.

I was writting a quite common TT muncher. It looked pretty much like:

macro_rules! i_am_a_tt_muncher {

( [ $( $state:tt )* ], let $var_name = $( $tail:tt )* ) => {

// ... code to be written there ...

};

/* Not shown: a lot of similar and unreadable match arms */

}

As I was a bit too tired, I wrote the following expansion code:

macro_rules! i_am_a_tt_muncher {

( [ $( $state:tt )* ], let $var_name = $( $tail:tt )* ) => {

i_am_a_tt_muncher! {

[ /* some new state */ ],

let $var_name = $( $tail:tt )*

}

};

}

I was so tired that I rewrote the pattern and forgot two things:

- as we have processed the

let $var_name =, we should not include it in the remaining input while recursing, - we are expanding an additional

: ttfor each remaining token.

As a result, each time we were matching that one rule, we started infinitely recursing, multiplying the number of tokens to process by three at each recursion.

I saved the file, rust-analyzer triggered a cargo check, which triggered a macro expansion of a unit test, which triggered an infinite macro recursion, which quickly ate all my computer's RAM. Visual Studio Code started getting less and less responsive. One killall rustc later, my laptop came back to its original super beefy state. I had to reopen my crate with vi to diagnose and fix the problem.

Final thoughts

As they wanted to guarantee that declarative macros eventually stop expanding, the Rust designers added a recursion limit. This limit is great: if someone accidentally writes a macro that infinitely recurses, then the compilation halts and no CPU core gets indefinitely hurt in the process.

However, this limit is not sufficient: while we are guaranteed that the compilation eventually finishes, we have no clue of how many resources are needed to actually get there.

The only solution I can think of is to limit the number of tokens that can be passed to a macro. While it technically is a breaking change, this should not impact already-existing code if this limit is high enough.